Caution: This article discusses APIs that are not yet fully standardized and still in flux. Be cautious when using experimental APIs in your own projects.

Introduction

Filters are a powerful tool that web authors can use to achieve interesting visual effects. In this article we’ll cover the history of filter effects, what they do and how to use them. We’ll cover examples of all the predefined filters defined for CSS with some examples. We’ll also cover performance considerations for using them on desktop and mobile devices since knowing the speed impact of filters is important for a good user experience. Finally we’ll review the current state of implementation in modern browsers.

The past, present and future of filter effects

Filter effects originated as part of the Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) specification. They were created to apply a number of different pixel based image effects to a vector drawing. Over time as browser vendors added SVG capabilities into their browsers, the usefulness of filters became evident. Robert O’Callahan from Mozilla came up with the brilliant idea of using SVG filters through the application of CSS to ‘normal’ HTML content. Robert prototyped an early version that showed how powerful the combination of filters and CSS styling could be. The CSS and SVG working groups in the W3C decided to harmonize the use of filters for both HTML and SVG via CSS styling, and thus the ‘filter’ property for CSS was born. Right now a joint task force of people working on CSS and SVG is doing a ton of work to make filters universally useful. You can find the current specification for all this stuff here.

A new life for the ‘filter’ CSS property

Deja Vu sometimes strikes a web developer when seeing ‘filter’ in CSS styles. This is due to the fact that old versions of Internet Explorer had a ‘filter’ property exposed via CSS to perform some platform specific functionality. This has been deprecated in favor of the standard ‘filter’ property which is now part of CSS3. So when you see ‘filter’ out in the wild on some old web pages, there’s no need to be confused. The new ‘filter’ property is where all the action is, and new versions of IE are implementing it just the same as all modern browsers.

How filters work

So what does a filter do exactly? The easiest way to think of a filter is as a post processing step that does something magical after all your page content has been laid out and drawn.

When a browser loads a web page it needs to apply styles, perform layout and then render the page so there’s something to look at. Filters kick in after all those steps and just before the page is copied to the screen. What they do is take a snapshot of the rendered page as a bitmap image, then perform some graphics magic on the pixels in the snapshot and then draw the result over the top of the original page image. One way to think of them is like a filter placed on the front of a camera lens. What you’re seeing through the lens is the outside world modified by the effect of the filter.

This of course means that there’s time consumed when drawing a page with filters on it, but using them properly will have minimal impact on the speed of your site.

Also, just as you can stack a number of filters in front of each other on your camera lens, you can apply an arbitrary number of filters one after the other to achieve all sorts of effects.

Filters defined using SVG and CSS

Since filters originally came from SVG there are different ways to define and use them. SVG itself has a

Most of the CSS filters can be expressed in terms of SVG filters, and CSS also allows you to reference a filter specified in SVG if you want. The CSS filter designers have taken great pains to make the application of a filter easier for web authors, and so this article will just cover the filters available directly from CSS, ignoring the SVG definitions for the time being.

How to apply a CSS filter

Note: The description and examples below use the official W3C syntax that will be available in all modern browsers eventually. To use filters now, you need to use the vendor prefixed version of the ‘filter’ property. But don’t worry there’s an easy way to handle that at the end of this article.

Using filters from CSS is done by using the ‘filter’ property applied to any visible element on your web page. For a very simple example you could write something like

div { +filter: grayscale(100%); }

and that would make the content inside all <div> elements on the page turn gray. Great for making your page look like a TV image from the 1940s.

Most filters take some form of parameter to control how much filtering is done. So for example if you wanted to style your content to be half way between the original color and a grayscale version you’d do it like this:

div { +filter: grayscale(50%); }

If you want to apply a number of different filters one after another, it’s easy - just place them in order in your CSS like so:

div { +filter: grayscale(100%) sepia(100%); }

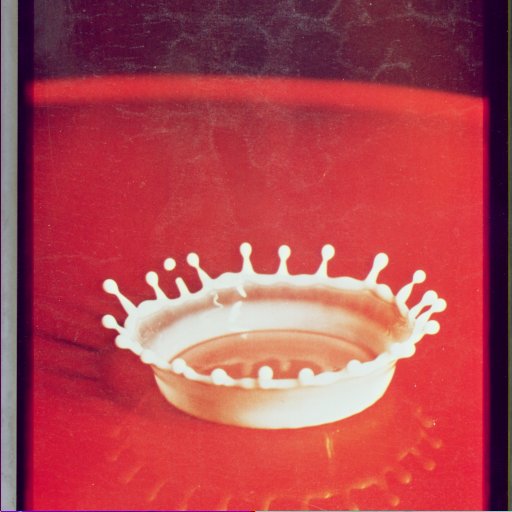

That example will first make all the original color grayscale and then apply a sepia effect, and would end up looking like:

With the flexibility available for applying filters one after the other, all sorts of effects can be achieved - it’s totally up to your imagination to experiment with creating amazing results.

What filters effects are available using CSS

So the original SVG filter mechanism is both powerful but at the same time can be daunting to use. Because of that, CSS introduces a bunch of standard filter effects that make using them really easy.

Let’s take a look at each of them and see what they do.

- grayscale(amount)

-

This converts color in our input image to a shade of gray. The ‘amount’ applied controls how much gray conversion is applied. If it’s 100% then everything will be a shade of gray, if it’s 0% the colors are unchanged. You can use a floating point number here if you prefer it over percentages, i.e. 0 works the same as 0% whilst 1.0 works the same as 100%.

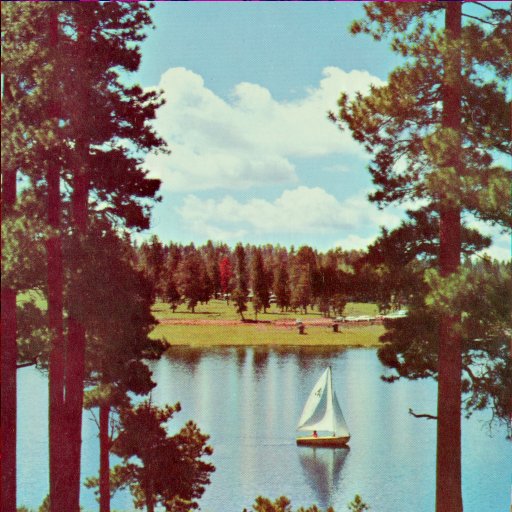

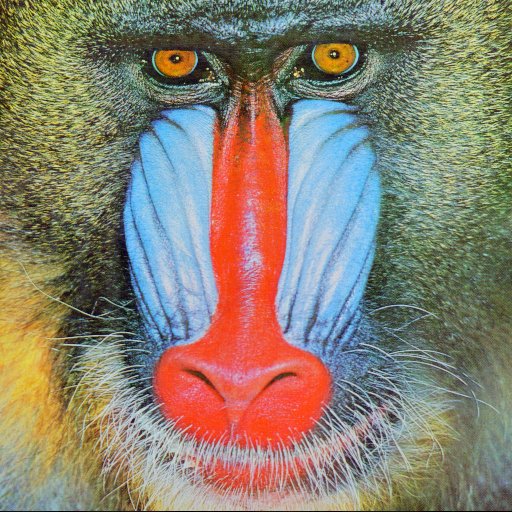

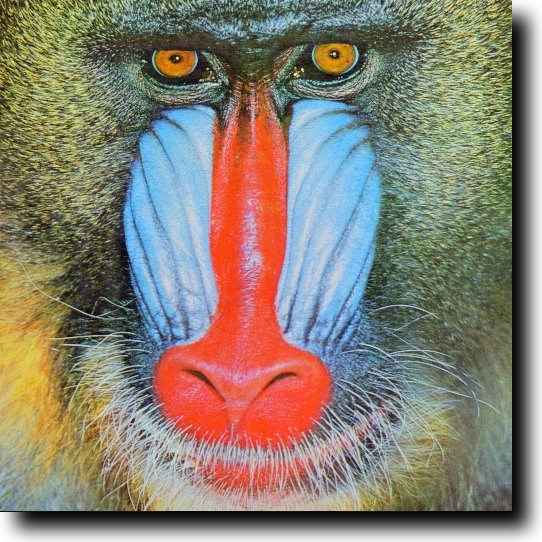

Original

grayscale(100%) - sepia(amount)

-

This gives the colors passed in a sepia tinge like in old photographs. The ‘amount’ applied works in the same way as for the ‘grayscale’ filter - namely 100% makes all the colors completely sepia toned and smaller values allow the effect to be applied in smaller proportions.

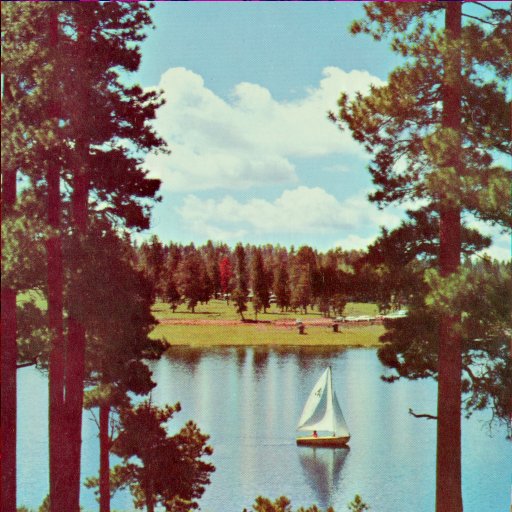

Original

sepia(100%) - saturate(amount)

-

This applies a color saturation effect to the colors which makes them look more vivid. It’s a cool effect that can make photos look like posters or cartoons.This effect also allows you to use a value greater than 100% to really emphasize the saturation. Definitely an effect that can make things look pretty funky!

Original

saturate(10) Note: In Chrome version 19, the saturate() function takes an integer (without the percentage sign) instead of the decimal or percentage, as per the W3C spec. Not to worry, this known bug will be fixed.

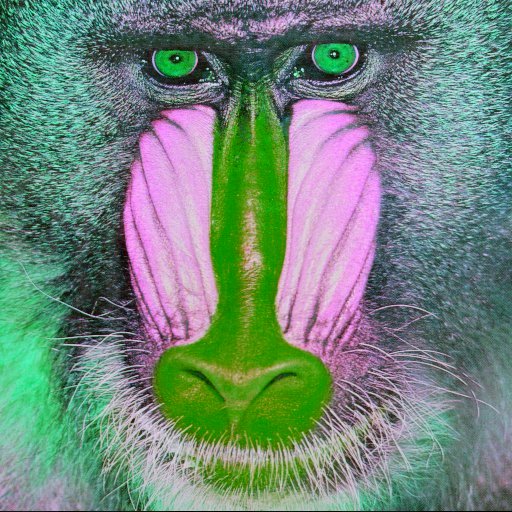

- hue-rotate(angle)

-

This one is a bit of a color geek effect that can be used for interesting results. What it does is shift the colors around to make an input image look completely different. If you can imagine a color spectrum going from red to violet around a color wheel, then this effect takes the original color on the wheel as input and rotates it by the ‘angle’ parameter to produce the color on the wheel to which it rotated as the output color value. So all the colors in the image are shifted by the same 'angle' on the wheel. This is of course a simplification of what it does, but hopefully close enough that it makes sense.

Original

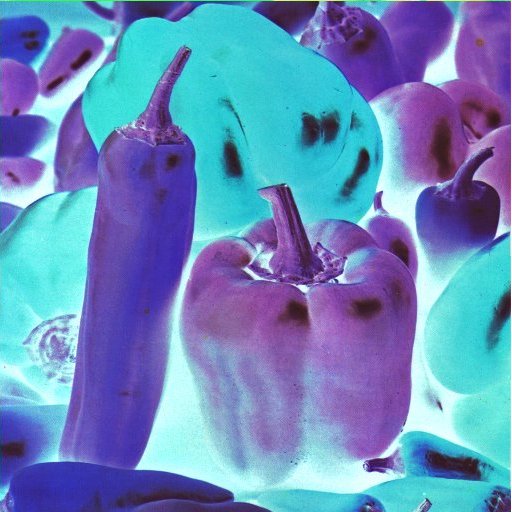

hue-rotate(90deg) - invert(amount)

-

This effect flips the colors - so that if the ‘amount’ applied is 100% the output looks like a photo negative back from the old film days of cameras! Just like before, using values smaller than 100% will progressively apply the invert effect.

Original

invert(100%) - opacity(amount)

-

If you want the content being filtered to look semi-transparent, this is the one for you. The ‘amount’ value defines how opaque the output will be. So a value of 100% is completely opaque so the output will be exactly the same as the input. As the value drops below 100% the output image will become less opaque (more transparent) and you’ll see less and less of it. This of course means if it overlaps something else on the page, the stuff underneath will start to become visible. An ‘amount’ of 0% means it will completely disappear - but note, you can still get events like mouse clicks etc. to happen on completely transparent objects so this is handy if you want to create clickable areas without displaying anything.

This works the same as the ‘opacity’ property you already know. In general the CSS ‘opacity’ property isn’t hardware accelerated, but some browsers that implement filters using hardware acceleration will accelerate the filter version of opacity for much better performance.

Original

opacity(50%) - brightness(amount)

-

This is just like the brightness control on your TV. It adjusts the colors between completely black and the original color in proportion to the ‘amount’ parameter. If you set this one to 0% you’ll see nothing but black, but as the value goes up towards 100% you see more and more of the original image brightening up, until you hit 100% where it’s the same as the input image. Of course you can just keep going - so setting something like 200% will make the image twice as bright as the original - great for adjusting those low light shots!

Original

brightness(140%) - contrast(amount)

-

More controls from your TV set! This will adjust the difference between the darkest and lightest parts of the input image. If you use 0% you end up with black just like with ‘brightness’, so not too interesting. However as you increase the value towards 100% the difference in darkness changes until you hit 100% and it’s the original image again. You can also go beyond 100% for this effect too, which increases the difference between light and dark colors even more.

Original

contrast(200%) - blur(radius)

-

If you want a soft edge for your content, you can add a blur. This one looks like the classic Vaseline on a sheet of glass look that used to be a popular movie making technique. It smudges all the colors together and spreads their effect out - kind of like when your eyes are out of focus. The ‘radius’ parameter affects how many pixels on the screen blend into each other, so a larger value will create more blur. Zero of course leaves the image unchanged.

Original

blur(10px) - drop-shadow(shadow)

-

It’s so nice to be able to make your content look like it’s outside in the sun with a shadow on the ground behind it, and that of course is what ‘drop-shadow’ does. It takes a snapshot of the image, makes it a single color, blurs it, then offsets the result a bit so it looks like a shadow of the original content. The ‘shadow’ parameter passed in is a bit more complicated than just a single value. It is a series of values separated by a space - and some values are optional too! The ‘shadow’ values control where the shadow is placed, how much blur is applied, the color of the shadow, etc. For full details of what the ‘shadow’ values do, the CSS3 Backgrounds specification defines ‘box-shadow’ in great detail. A few examples below should give you a decent idea of what the various possibilities are.

drop-shadow(16px 16px 20px black)

drop-shadow(10px -16px 30px purple) This is another filter operation that is similar to existing CSS functionality available via the ‘box-shadow’ property. Using the filter approach means that it may get hardware accelerated by some browsers as we described for the ‘opacity’ operation above.

- url referencing SVG filters

-

Since filters originated as part of SVG, it’s only logical that you should be able to style your content using an SVG filter. This is easy with the current ‘filter’ property proposal. All filters in SVG are defined with an ‘id’ attribute that can be used to reference the filter effect. So, to use any SVG filter from CSS all you need to do is reference it using the ‘url’ syntax.

For example, the SVG markup for a filter could be something like:

then from CSS you could do something as simple as:<filter id=”foo”>...</filter>div { +filter: url(#foo); }and voila! All the <div>s in your document will be styled with the SVG filter definitions.

- custom (coming soon)

-

Coming soon on the horizon are custom filters. These tap into the power of your graphics GPU to use a special shading language to perform amazing effects bounded only by your own imagination. This part of the ‘filter’ specification is still under discussion and in flux, but as soon as this starts to come to a browser near you, we’ll be sure to write more about what is possible.

Performance considerations

One thing that every web developer cares about is performance of their web page or application. CSS filters are a powerful tool for visual effects, but at the same time might have an impact on the performance of your site.

Understanding what they do and how this affects performance matters, especially if you want your site to work well on mobile devices if they support CSS filters.

Firstly, not all filters are created equal! In fact, most filters will run really quickly on any platform and have very minor performance impact. However, filters that do any kind of blurring tend to be slower than the others. This of course means ‘blur’ and ‘drop-shadow’. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use them but understanding how they work might help.

When you do a ‘blur’, it mixes the colors from pixels all around the output pixel to generate a blurred result. So, say if your ‘radius’ parameter is 2, then the filter needs to look at 2 pixels in every direction around each output pixel to generate the mixed color. This happens for each output pixel, so that means a lot of calculations that just get bigger when you increase the ‘radius’. Since ‘blur’ looks in every direction, doubling the ‘radius’ means you need to look at 4 times as many pixels so in fact it’s 4 times slower for each doubling of the ‘radius’. The ‘drop-shadow’ filter contains a ‘blur’ as part of its effect, so it too behaves just like ‘blur’ when you change the ‘radius’ and ‘spread’ parts of the ‘shadow’ parameter.

All is not lost with ‘blur’ since on some platforms it’s possible to use the GPU to accelerate it, but that’s not necessarily going to be available in every browser. When in doubt the best thing is to experiment with the ‘radius’ that gives you the effect you want, then try to reduce it as much as possible while still maintaining an acceptable visual effect. Tuning this way will make your users happier especially if they use your site from a phone.

If you’re using ‘url’ based filters that reference SVG filters, they can contain any arbitrary filter effect so be aware that they too could be slow, so try to make sure you know what the filter effect does and experiment on a mobile device to make sure the performance is OK.

Availability in modern browsers

Right now a number of the CSS ‘filter’ effects are being made available in WebKit based browsers and Mozilla. We expect to see them soon in Opera as well as IE10. As the specification is still under development, some browser vendors have implemented this stuff using vendor prefixes. So in WebKit you need to use ‘-webkit-filter’, in Mozilla you will need to use ‘-moz-filter’ and keep your eye out for other browser implementations as they appear.

Not all browsers will support all filter effects right away, so your mileage will vary. Presently, the Mozilla browser supports only the 'filter: url()' function - without the vendor prefix, as that implementation pre-dates the other effects functions.

We’ve summarized the CSS filter effects available in the various browsers below with rough performance indicators for when they’re implemented in software. Note, that a number of modern browsers are beginning to implement these in hardware (GPU accelerated). When these are built with GPU support, performance will be greatly improved for the slower effects. As usual, testing on different browsers is the best way to evaluate the performance.

| Filter effect | Browser support | Performance |

|---|---|---|

grayscale | Chrome | very fast |

sepia | Chrome | very fast |

saturate | Chrome | very fast |

hue-rotate | Chrome | fast |

invert | Chrome | very fast |

opacity | Chrome | can be slow |

brightness | Chrome | fast |

contrast | Chrome | fast |

blur | Chrome | slow unless accelerated |

drop-shadow | Chrome | can be slow |

url() | Chrome, Mozilla | Varies, fast to slow |

Other good resources

An awesome interactive abstract painting with filters application which lets you experiment and share your artwork

Be sure to check out Eric Bidelman’s excellent interactive filter page

A great tutorial about filters with examples

The official W3C Filter Effects 1.0 draft specification https://dvcs.w3.org/hg/FXTF/raw-file/tip/filters/index.html

Example UI created using filters